What Percent Of Registered Voters Are Republican

The United States holds a presidential ballot every four years, but it's non only the candidates and issues that change from ane campaign cycle to the next. The electorate itself is in a slow but constant country of flux, too.

The profile of the U.S. electorate can alter for a multifariousness of reasons. Consider the millions of Americans who have turned eighteen and tin vote for president for the start time this year, the immigrants who have become naturalized citizens and tin can bandage ballots of their ain, or the longer-term shifts in the country's racial and indigenous makeup. These and other factors ensure that no two presidential electorates wait exactly the same.

So what does the 2020 electorate look like politically, demographically and religiously as the race between Republican President Donald Trump and Democrat Joe Biden enters its concluding days? To answer that question, here's a roundup of recent Pew Research Center findings. Unless otherwise noted, all findings are based on registered voters.

Party identification

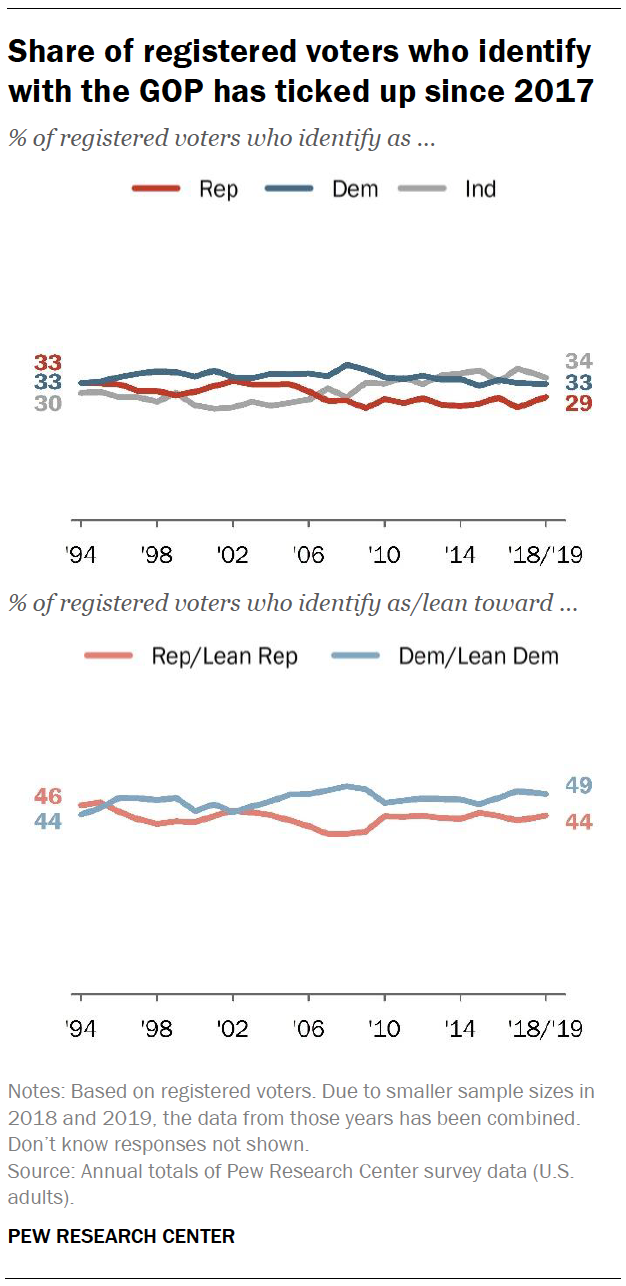

Around a 3rd of registered voters in the U.S. (34%) identify as independents, while 33% place as Democrats and 29% place as Republicans, according to a Center analysis of Americans' partisan identification based on surveys of more than 12,000 registered voters in 2018 and 2019.

Well-nigh independents in the U.S. lean toward one of the two major parties. When taking independents' partisan leanings into business relationship, 49% of all registered voters either identify every bit Democrats or lean to the political party, while 44% identify as Republicans or lean to the GOP.

Party identification amid registered voters hasn't inverse dramatically over the past 25 years, but there take been some small-scale shifts. I such shift is that the Autonomous Party'south reward over the Republican Party in political party identification has become smaller since 2017. Of form, merely considering a registered voter identifies with or leans toward a particular political party does not necessarily mean they will vote for a candidate of that party (or vote at all). In a study of validated voters in 2016, five% of Democrats and Democratic leaners reported voting for Trump, and iv% of Republicans and GOP leaners reported voting for Hillary Clinton.

Race and ethnicity

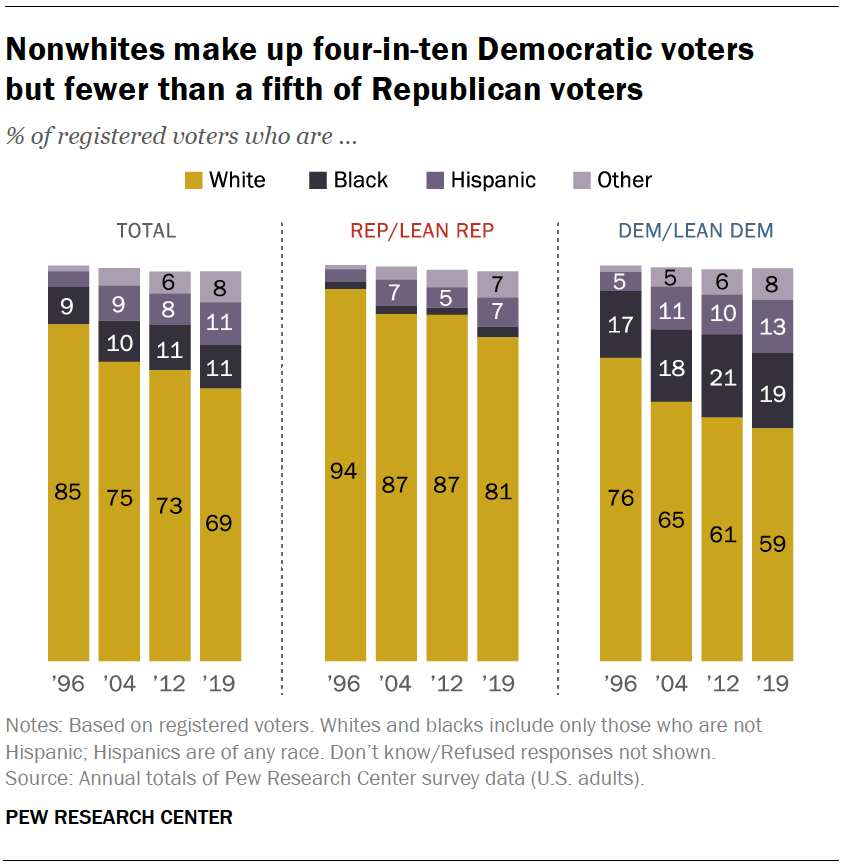

Non-Hispanic White Americans make up the largest share of registered voters in the U.S., at 69% of the full as of 2019. Hispanic and Black registered voters each account for 11% of the total, while those from other racial or ethnic backgrounds account for the residue (8%).

White voters account for a diminished share of registered voters than in the past, declining from 85% in 1996 to 69% alee of this year'south ballot. This change has unfolded in both parties, but White voters have consistently accounted for a much larger share of Republican and Republican-leaning registered voters than of Democratic and Autonomous-leaning voters (81% vs. 59% as of 2019).

The racial and ethnic composition of the electorate looks very different nationally than in several primal battleground states, co-ordinate to a Heart analysis of 2018 data based on eligible voters – that is, U.S. citizens ages 18 and older, regardless of whether or not they were registered to vote.

White Americans accounted for 67% of eligible voters nationally in 2018, but they represented a much larger share in several key battlegrounds in the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic, including Wisconsin (86%), Ohio (82%), Pennsylvania (81%) and Michigan (79%). The contrary was truthful in some battleground states in the West and S. For example, the White share of eligible voters was below the national average in Nevada (58%), Florida (61%) and Arizona (63%). You tin can see racial and indigenous breakdown of eligible voters in all 50 states – and how it changed betwixt 2000 and 2018 – with this interactive characteristic.

Age and generation

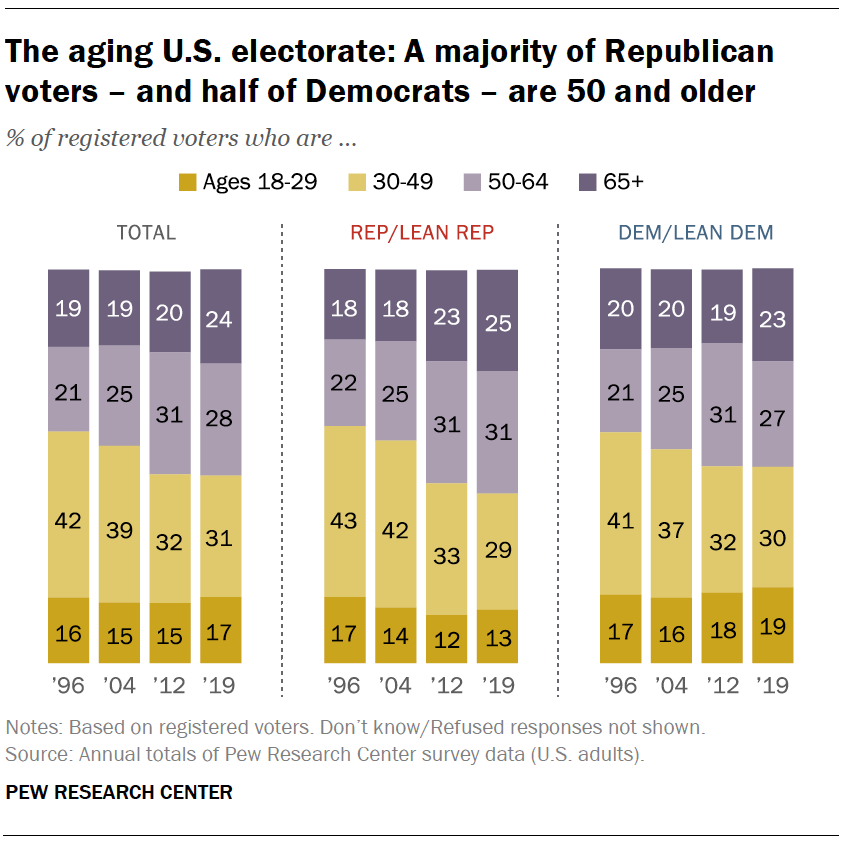

The U.S. electorate is aging: 52% of registered voters are ages fifty and older, up from 41% in 1996. This shift has occurred in both partisan coalitions. More than half of Republican and GOP-leaning voters (56%) are ages 50 and older, upward from 39% in 1996. And amidst Democratic and Democratic-leaning voters, half are fifty and older, up from 41% in 1996.

Some other style to consider the crumbling of the electorate is to look at median age. The median age amongst all registered voters increased from 44 in 1996 to l in 2019. It rose from 43 to 52 amidst Republican registered voters and from 45 to 49 among Democratic registered voters.

Despite the long-term aging of registered voters, 2020 marks the start time that many members of Generation Z – Americans born later 1996 – will be able to participate in a presidential ballot. I-in-10 eligible voters this yr are members of Generation Z, up from only 4% in 2016, according to Pew Research Center projections. (Of course, not all eligible voters end up registering and really casting a election.)

Education

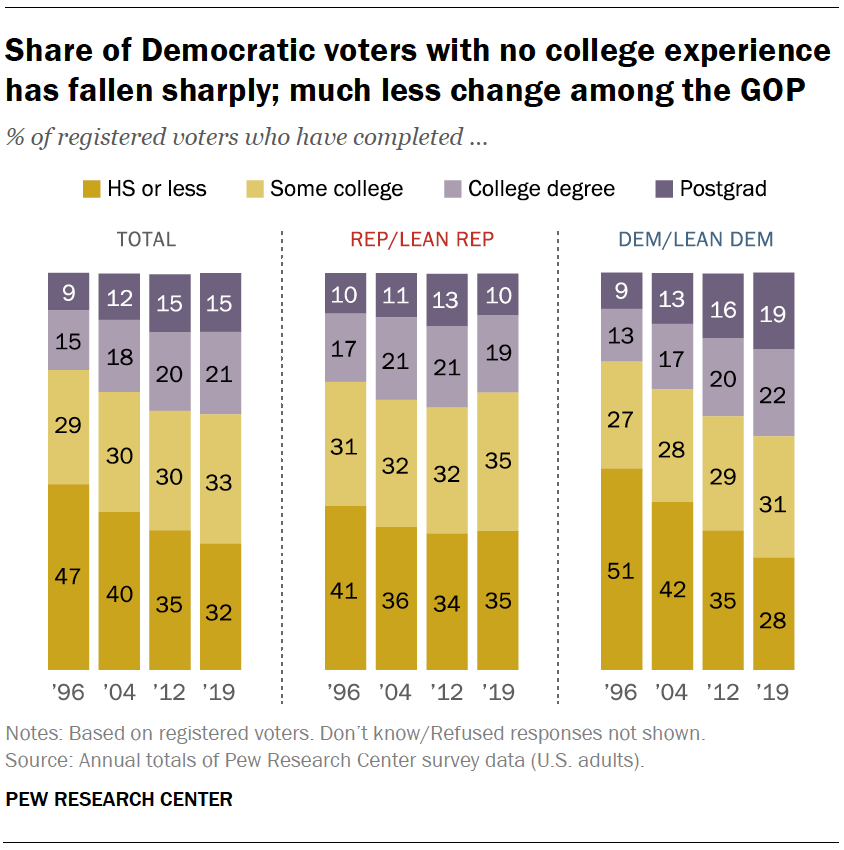

Around 2-thirds of registered voters in the U.S. (65%) do not accept a higher degree, while 36% practise. But the share of voters with a college caste has risen essentially since 1996, when 24% had 1.

Voters who identify with the Autonomous Party or lean toward it are much more likely than their Republican counterparts to have a college degree (41% vs. 30%). In 1996, the reverse was true: 27% of GOP voters had a college degree, compared with 22% of Democratic voters.

Religion

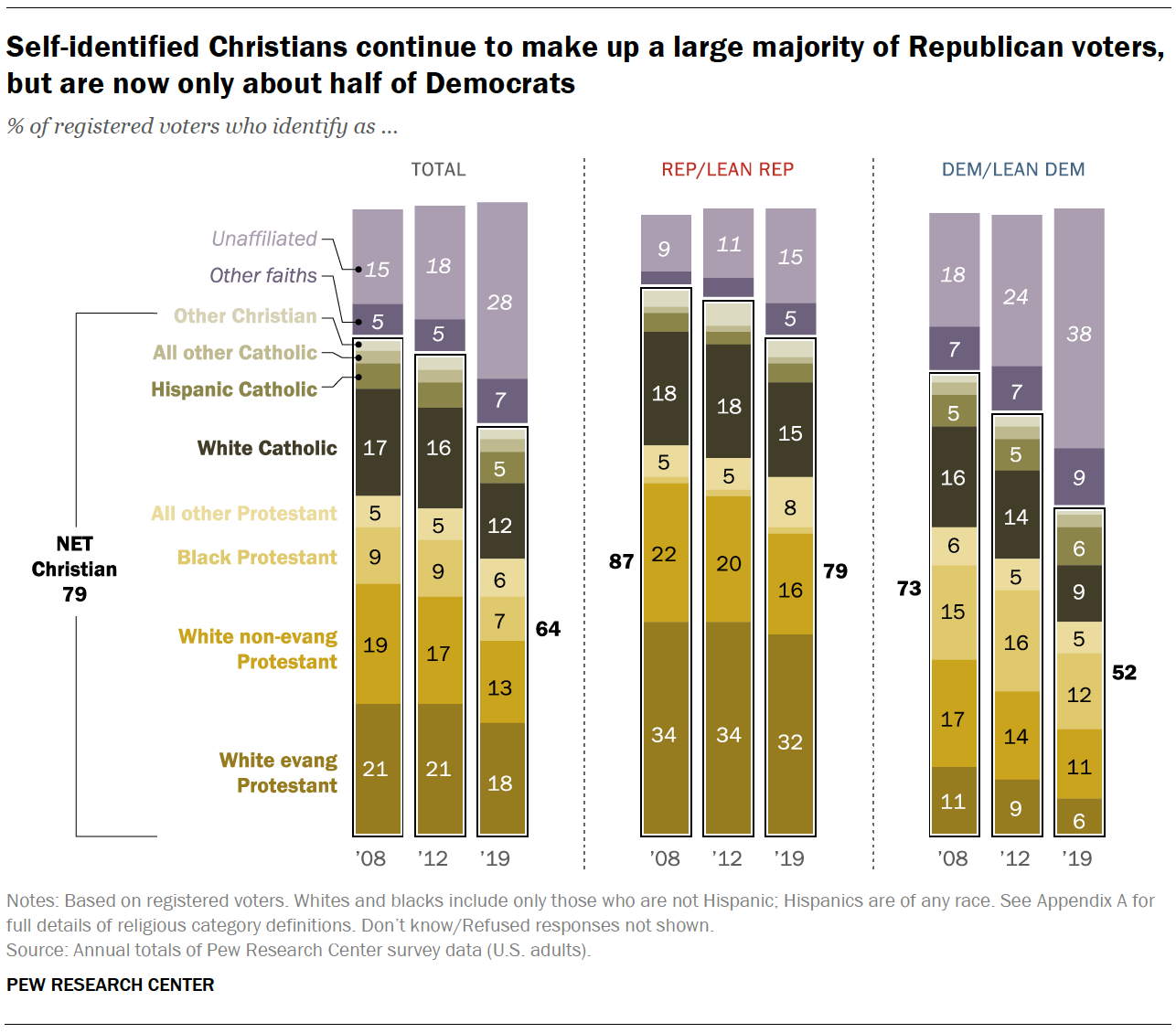

Christians account for the majority of registered voters in the U.Due south. (64%). But this figure is down from 79% every bit recently as 2008. The share of voters who place as religiously unaffiliated has nigh doubled during that bridge, from 15% to 28%.

The share of White Christians in the electorate, in particular, has decreased in recent years. White evangelical Protestants account for 18% of registered voters today, downwardly from 21% in 2008. During the same period, the share of voters who are White non-evangelical Protestants fell from 19% to xiii%, while the share of White Catholics fell from 17% to 12%.

Around viii-in-ten Republican registered voters (79%) are Christians, compared with about half (52%) of Democratic voters. In plough, Democratic voters are much more than probable than GOP voters to identify as religiously unaffiliated (38% vs. 15%).

The fundamental question: What about voter turnout?

Surveys can provide reliable estimates about registered voters in the U.South. and how their partisan, demographic and religious profile has changed over time. Merely the critical question of voter turnout – who will be motivated to cast a election and who will not – is more difficult to answer.

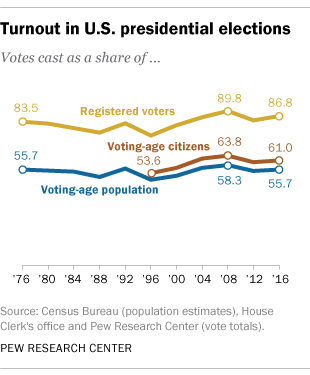

For i affair, not all registered voters end up voting. In 2016, effectually 87% of registered voters cast a ballot, co-ordinate to a Pew Research Center analysis of Census Agency data shortly after that year's election.

Likewise, voter turnout in the U.S. is not a constant: It tin and does alter from one election to the next. The share of registered voters who cast a ballot was higher in 2008 than four years ago, for example.

Turnout also varies by demographic factors, including race and ethnicity, historic period and gender. The turnout charge per unit among Black Americans, for case, exceeded the rate amid White Americans for the first time in the 2012 presidential election, but that design did not concur iv years later.

And so what does all this hateful for 2020? There are some early indications that overall turnout could reach a record high this year, only as turnout in the midterms two years ago reached its highest bespeak in a century. But 2020 is far from an ordinary twelvemonth. The combination of a global pandemic and public concerns about the integrity of the election have created widespread uncertainty, and that doubtfulness makes it fifty-fifty more hard than usual to appraise who will vote and who won't.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/10/26/what-the-2020-electorate-looks-like-by-party-race-and-ethnicity-age-education-and-religion/

Posted by: hoffmanmrsooduraske.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Percent Of Registered Voters Are Republican"

Post a Comment